Much of Gibbet Hill lies outside the parish of Brentor but its position on the east side of the parish, adjacent to West Blackdown, means that it is a favourite place for many Brentor residents.

This article is part of a larger article ‘The King Way: Part 2 – Blackdown to Nodden Gate‘ published in March 2021 on the ‘A Walk in English Weather’ website. It is reproduced here by permission of the author, Sharon Gedye. You can see the full article by clicking here.

Gibbet Hill does not lie on the King Way but dominates it and I sense its history is intertwined with this postal route. In order to explain I am going to explore a bit of gibbeting history.

Gibbeting was the act of hanging people in chains or in a metal cage. It was used to distinguish the death penalty used for any one of about 220 ordinary crimes from those of the most heinous. Gibbeting was used for murder, robbery, arson and riot. Criminals guilty of these ‘worst of the worst’ offences could also be sentenced to post-mortem dissection. Eighty per cent of felons were dealt with this way, but gibbeting accounted for the other 20%. Between the 1720s and 1830s this translated into about 375 men (Tarlow and Dyndor, 2015). Spread over the whole of the country, that isn’t very many. Gibbeting was therefore a relatively rare practice.

Before the 18th C criminals could be gibbetted alive but in the 1700s they were executed first and hung in a cage already dead. The chained or caged body would be transported to the gibbet site and raised on a very high pole of about 30ft tall. Bodies would be left to gradually decompose and gibbets were designed with enough movement to allow the cage to creak and clank as it swung in the wind. The lofty altitude and noises were thus purposefully designed to bring attention to the fate of the criminal and the importance of justice. The gibbet could hang for many years and so, whilst gibbeting might be rare, its persistence in the landscape gave it a lengthy presence.

Given the rarity of gibbeting, why is there a Gibbet Hill located here in this remote part of the Dartmoor periphery? Tarlow and Dyndow (2015) state three key reasons for the siting of gibbets:

- Practicality – common land was often favoured because it enabled crowds to form; gibbeting was a popular spectacle so it was necessary that crowds did not block thoroughfares nor trample crops.

- Visibility – hills were popular locations because they maximised conspicuity.

- Proximity – gibbets were often hung near the scene of the crime in order to link justice to the crime. Highway robbery and mail robbery therefore meant that gibbets occupied locations near important roads.

Gibbet Hill satisfies all of these locational factors, and in relation to the point about proximity, is suggestive that the crime of highway robbery was problematic here. This is supported by local oral histories of caged outlaws and highwaymen left to starve.

It is also highly significant that gibbeting at this spot, which satisfies the mantra ‘location, location, location’ is also close to Lydford. Here until the early 19th C, and for many centuries before, was the notoriously dreadful criminal court and gaol. Crossing (1987, writing c. 1901) helps shed light on the relationship between gaol and gibbet. He says:

“It may be remarked that one of the gates of Black Down, at the end of Burn Lane, is still known as Ironcage Gate”

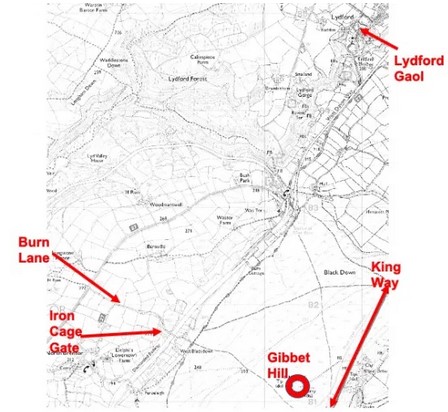

Map showing Gibbet Hill and its relationship to the King Way route, the location of Ironcage Gate at the end of Burn Lane, and Lydford Gaol. (Map from DCC Environment Viewer)

“It may be remarked that one of the gates of Black Down, at the end of Burn Lane, is still known as Ironcage Gate”

Criminals would no doubt be brought on the road from Lydford to Burn Land and then onwards to the hill top. Only about 100 yards from Ironcage Gate is shown on old maps a smithy. I wonder if it was here that the iron cage was made and the convicted body incarcerated? I like how this historical record from Crossing joins the dots of the route between Lydford Gaol, Ironcage Gate, and hoisting spot high on the hill, where the criminal cadaver’s notoriety was left to ferment in the breeze.

Gibbeting was a popular spectacle, drew big crowds, and created a carnival atmosphere that could last for days (Tarlow and Dyndor, 2015). Whilst the relatively remote situation of Gibbet Hill would set limits on the size of crowds, even here there would likely be a large gathering to view and celebrate this ultimate punishment of the state. The power of the celebration, the enduring legacy of the body swinging in the cage for many years after, and the stench and and noise coming from the gibbet cemented its ill-fame through enduring place names and the oral histories associated with place.

For those who want to enjoy the macabre narratives associated with Gibbet Hill I recommend Legendary Dartmoor – Dartmoor’s Gibbet Hill , Hemery (1983, p996-997) and Charles Kingley’s depiction in Westward Ho! of the outlaw Gubbins family in this location, thought to have some basis in the real history of Gibbet Hill country.